Don’t Cook the Frog: Lessons from a Nonprofit’s Near-Death Experience

“An organization that is not capable of perpetuating itself has failed.” — Peter Drucker

| The Idea in Brief | The Idea in Practice |

|---|---|

| The more than 1.5 million nonprofits in the U.S. are an essential safety net for those in need. They care for the neglected, feed the hungry and find jobs for the unemployed. Unfortunately, many nonprofits struggle to survive, let alone thrive. According to Guidestar, half of all nonprofits are operating with less than one month’s cash reserves, and 7% to 8% are technically insolvent.

Urban legend holds if you place a frog in a pot of boiling water, it will leap out. But if the frog is placed into a pot of tepid water, and the temperature is slowly increased, it will acclimate until the water boils, cooking the frog.

Jack Eckerd, philanthropist and drugstore pioneer, founded Eckerd Connects in 1967 to give troubled youth a second chance. By 2007, the nonprofit ran 18 residential wilderness camps and served 9,500 youth annually. However, state juvenile justice agencies had begun referring fewer youth to the camps because of the arrival of lower-cost community-based services. As a result, Eckerd Connects became a teetering nonprofit using roughly $2.4 million a year from its endowment to offset operating expenses.

Eckerd Connects is an example of a nonprofit that was almost “cooked” but managed to escape the pot. It did so by adhering to the following principles:

Like all organizations, nonprofits must remain healthy and agile to fulfill their missions. For those struggling, this means embarking on a transformation journey. Hopefully, Eckerd Connects’ story can help fellow nonprofits deliver on the promise of change. |

Accept reality

It is hard admitting services that were successful for decades have lost relevance. Change can only take root when nonprofit leaders embrace their actual situation and pledge to make decisive changes based on current conditions, not what they wish things to be. Confronted with mounting losses, the Eckerd Board faced the situation and committed to walking a new path.

Rediscover true north “The kids,” as Mr. Eckerd called them, have always been at the heart of Eckerd’s mission. But after Mr. Eckerd passed in 2004, “the kids” slowly became “the camps.” A nonprofit must reconnect with its purpose if it is to evolve. For Eckerd, this meant prioritizing client needs over preserving the camps.

Pursue a moonshot In 1962, President John F. Kennedy famously said, “We choose to go to the moon,” focusing the nation’s trailblazing spirit on perhaps the most ambitious goal ever dreamt by humankind. Declaring a so-called “moonshot” is intimidating, but it unifies an organization around a common cause and forces its employees to think and act differently — often taking actions that would normally not even be considered. In 2010, Eckerd stated its 2020 Vision was to serve 20,020 clients annually despite serving half as many at the time.

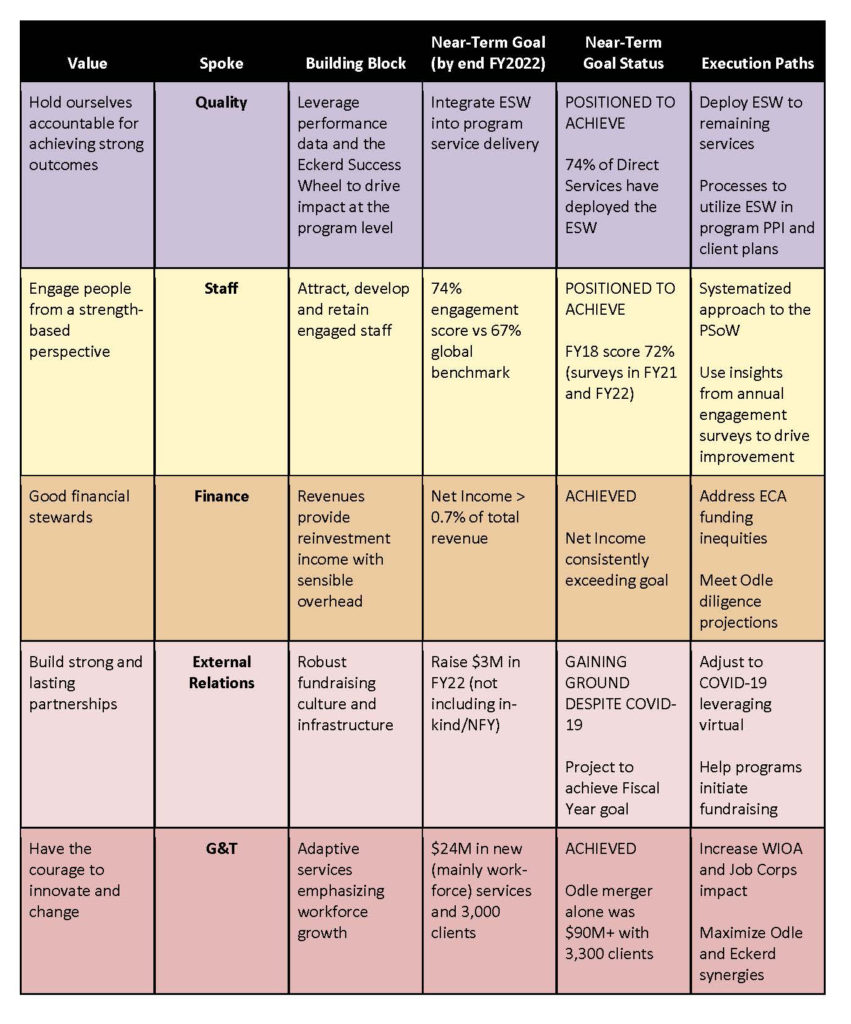

Operationalize your values Values must be a nonprofit’s heartbeat. This is why Eckerd created the Eckerd WheelTM, which maps Eckerd’s values onto five operational “Spokes”— each with its own key performance indicators and a designated leader — and has Eckerd’s clients as the wheel’s hub. Keeping this image in mind allowed Eckerd’s leadership to visualize the coordination of all resources to fulfill its mission.

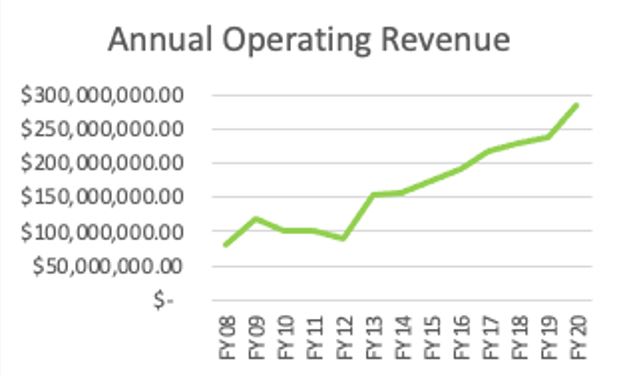

Strategy is nothing without execution A nonprofit must articulate its milestones, resource allocations and execution paths in simple terms. It must also have an easy-to-use system that steers implementation. And, of course, it must act, not just plan. Between 2007 and 2020, Eckerd transformed from a $79 million camp operator to a $350 million community provider by following a one-page Strategic Snapshot.

Never stop adapting One of Eckerd’s values is having the courage to change, which allows it to continuously adapt its programs to better serve clients. By adhering to this value, since 2007, Eckerd has transformed from a juvenile justice camp operator to a child welfare system of care administrator and eventually to a leading workforce services provider.

Expand deliberately Beginning in 2014, Eckerd’s leadership pursued a series of acquisitions that to date have grown the organization’s annual revenue by roughly $126 million. Each acquisition was evaluated to align with the five Spokes of the Eckerd Wheel and to ensure it had the potential to benefit the clients and communities served by Eckerd.

Empathy is essential The stress of change can overwhelm staff and the Board. Do we really have to go in a different direction? Which programs will survive? Will valued employees still have jobs? Considering these kinds of questions, much less answering them, causes anxiety that must be recognized and attended to, not ignored. An organization can’t fix a problem it does not admit exists. Taking this honest and open approach allows nonprofit leaders to make and communicate difficult decisions expeditiously and with empathy, which is essential to successfully transforming the organization.

The middle is messy The middle part of change is a rollercoaster of volatility. Emotions ride up and down, tempers flare and physical exhaustion takes its toll. During this period, nonprofit leaders must maintain self-awareness about balancing work and life. |

On January 27, 2012, after 123 years, Chicago’s venerable social services agency Hull House closed its doors. At its peak, the nonprofit provided a range of services — including foster care, domestic violence counseling and job training — to about 60,000 clients a year. At the time of its closing, Hull House owed more than $3 million to vendors and landlords. Staff did not receive severance, earned vacation pay or healthcare, and for the thousands of families relying on Hull House for basic needs, all services stopped. Ten years earlier, Hull House’s annual revenue was over $40 million.

Urban legend holds if you place a frog in a pot of boiling water, it will leap out. But place a frog in a pot of tepid water and gradually increase the temperature, the frog will acclimate until the water boils, cooking the frog. It happens all the time. It nearly happened to Eckerd Connects.

Nonprofits are an essential safety net for those in need — caring for the neglected, feeding the hungry and finding jobs for the unemployed. In 2016, over 1.5 million nonprofits filed with the IRS. According to Guidestar, half of all nonprofits are operating with less than one month’s cash reserves, and 7% to 8% are technically insolvent.

For many nonprofits, dealing with the slowly heating pot of challenges that will eventually overwhelm them means summoning the courage to embark upon an arduous journey of change. But how does a nonprofit undertake fundamental change? What path does it take? What tools are needed? What core principles help map out actions? This paper will map a course through these challenges.

40 years in the wilderness

Jack Eckerd had an amazing life. A World War II pilot who flew over the Himalayas. Appointed by President Gerald Ford to lead the General Services Administration. In 1952, Mr. Eckerd bought three small drugstores and grew the business to over 1,500 stores before selling his shares. But Mr. Eckerd was most proud of his philanthropic work, especially his namesake nonprofit Eckerd Connects (Eckerd), which he founded to provide troubled youth a second chance.

Upset with state agencies placing youth in “training schools” that provided minimal therapeutic care, in 1967 Mr. Eckerd used his own money to build Eckerd’s first outdoor therapeutic program, or “camp.” An Eckerd camp was a 12- to 24-month residential program for youth involved in the juvenile justice system. Highly integrated with nature in a remote setting, camps offered a therapeutic milieu and caring staff. At the time, the camps were a major innovation over traditional residential services.

Over the next four decades, Eckerd grew to operate 25 residential programs — the majority employing the original camp model — across seven states. By 2007, Eckerd served 9,500 youth a year, with most of its $79 million in annual revenue coming from state juvenile justice contracts. However, between 2004 and 2007, the organization was using its endowment to offset operating expenses to the tune of about $2.4M per year. Quality declined as multiple programs were struggling and on corrective action plans. And camp attendance, Eckerd’s financial driver, began sliding as state agencies started contracting with lower-cost community-based service providers. Like a lot of nonprofits, Eckerd was feeling the heat of mounting problems.

Accept reality

Over 40 years, Eckerd cared for nearly 100,000 children. In several states, Eckerd helped facilitate the transition of residential services away from a punishment-oriented model to a therapy-centered approach. Staff were dedicated to the youth and proud of the work they did, sharing success stories of kids who turned their lives around after receiving a second chance.

It is difficult to admit something cherished for so long is now losing its relevance. All the stories and memories can form a haze over the truth residing out in the open. When the emotional investment is so high, it becomes easy, even normal, to brush off problems with ostensibly plausible reinterpretations of why things went awry. We are tempted to say a loss in attendance is a temporary dip that will correct when state agencies get more funding. That another year losing millions of dollars is just the cost of doing this work and serving others.

Some staff saw what was happening and tried their best to right the ship, but to little avail. They were overwhelmed by a tide of voices saying “this is how it has always been.” In the end, change can only take root when leadership acknowledges that the situation is worsening and there is no end in sight.

The Eckerd Board was traditionally composed of members and close friends of the Eckerd family. Their love for Mr. Eckerd and his nonprofit was palpable. Many had cherished memories of visiting the camps as children, hosting kids from the camps at their homes on Christmas Day, and watching Mr. Eckerd’s eyes tear up as he gave a child a big hug.

The organization’s individual success stories contrasted with a series of troubling financial and quality reports. When the Board asked staff why these things were happening and what was to be done, the organization found itself in a fog of circuitous justifications. Eckerd was in a figurative pot with the heat rising and sooner or later would be “boiled” unless it took a new path. The Board accepted the reality that for Eckerd to survive another four years, let alone another 40, decisive change was needed.

Rediscover true north

In 2008, after having five CEOs over the previous 10 years, the Board hired a new CEO tasked with changing Eckerd’s trajectory. The Board knew difficult decisions had to be made to ensure the survival of the organization, so it intentionally sought out a CEO with extensive turnaround experience.

The new CEO, David Dennis, came from a career in youth services and had once led the Oklahoma Office of Juvenile Justice. This background gave him firsthand knowledge of a shift that was taking place among state juvenile justice agencies, Eckerd’s main funding sources — they were moving away from residential programs toward lower-cost community-based services. Mr. Dennis envisioned a future originating not with salvaging Eckerd’s camps, but with returning to the organization’s raison d’être. Eckerd would start where Mr. Eckerd began four decades earlier, with “the kids.”

Eckerd’s outdoor therapeutic camp model was an innovation in residential services in 1967. The camps were cheaper than state-run training schools because youth stayed one to two years, not three to four. They produced better results, as their milieu was therapeutic versus punishment oriented. Located in bucolic settings, some with lakes for fishing, they had no razor-wire fences or barred windows. Staff lived with the youth and cared for them as their own. There was no comparison between a camp and a training school in 1967. Not only were camps better for kids, stakeholders and staff easily fell in love with the concept.

Mr. Eckerd’s own decisions for Eckerd were guided solely by what he considered to be the best interest of “the kids.” “The kids” were why he used his own money. However, after he passed in 2004, Eckerd’s “why” morphed gradually over time from “the kids” to “the camps,” with the camps achieving a near-sacred status in the nonprofit’s view of its mission by the time Mr. Dennis was hired in 2007.

This is not an uncommon nonprofit dilemma: An organization becomes so enamored with its services that it loses sight of why it exists. Reorienting Eckerd back toward its true north, “the kids,” required steering staff on a course that included, over time, closing most, if not all, of the camps.

This effort began with a series of hard conversations. Eckerd’s program leaders gathered together for a summit in which they discussed what had happened and how Eckerd would rekindle its commitment to “the kids.” Management also began a series of program visits with case workers, support staff and therapists. These conversations were an opportunity to discuss hard truths — including financial losses and slips in quality — as well as a vision of how Eckerd could more effectively serve children in their communities.

However, these conversations also led to heavy resistance from program leaders and others within Eckerd, who were concerned that the company was deviating too far from its original mission and Mr. Eckerd’s vision. Holding to Eckerd’s true north meant understanding that, while the organization must honor its past, the kids of 2007 deserved as innovative an approach as the kids of 1967 enjoyed. The Board backed Eckerd’s transformation from one of the largest nonprofit operators of camps to an organization focused on community-based services. But doing that required the organization to think big.

Pursue a moonshot

Pursuing an ambitious plan — a “moonshot” — feels scary, but it challenges an organization to execute in new, untried manners. People have to think differently, operate outside their comfort zone and do so with urgency, until what was first thought unimaginable becomes possible and later probable.

In 2009, Eckerd leadership announced Eckerd’s “2020 Vision,” a moonshot to serve 20,020 clients annually by 2020 — an ambitious goal, as Eckerd at the time was serving fewer than 10,000 clients a year, with the majority of its programs likely to close in due time. In effect, Eckerd had to add 20,020 clients and serve them via programs that the organization did not currently operate. The only way to scale to that many clients was through operating non-residential services that better met the needs and cultural realities of the current environment — in other words, transforming into a community-based provider.

Along with its 2020 Vision, Eckerd mapped out the transformation imperatives that would direct resource allocation and decision making over the coming years. The most critical of these: new program development resources that would be focused on community-based services. Eckerd also began engaging its funders on the gradual divestiture of the camps.

In 2007, Eckerd served 9,500 clients annually on revenues of $79 million and operated 25 juvenile justice residential programs, with 18 of these being camps. In 2020, Eckerd served nearly 40,000 clients on revenues of $340 million, with only one of the nonprofit’s original 25 residential programs remaining in operation — Camp E-Nini-Hassee, a six-month private pay program for girls. In addition to this camp, Eckerd operates myriad workforce development, child welfare, juvenile justice and mental health services across 21 states and the District of Columbia.

Operationalize your values

A nonprofit’s values must guide everything it does, from interacting with others to making decisions. So, Eckerd needed to engineer a means by which it could integrate these values into daily execution. From this imperative came the Eckerd Wheel — a Hub, which represents the children, families and communities Eckerd serves, and five Spokes, which represent the key operations carried out by the organization. To assure that Eckerd’s values were incorporated into its operations, a value was associated with each Spoke. The Eckerd Wheel became the focal point of decision-making for the entire Eckerd organization.

Eckerd’s operational Spokes and corresponding values are:

- Quality: Be accountable for achieving superior outcomes

- Staff: Engage people from a strength-based perspective

- Finance: Be good financial stewards

- External Relations: Build strong and lasting partnerships

- Growth & Transformation: Have the courage to change

Each Spoke has a designated champion on the Executive Leadership Team. Programs — the success of which are measured by a set of key performance indicators (KPIs) — use the five Spokes as a guide when conducting their daily operations, discussing challenges and opportunities internally and with headquarters staff.

Decisions made by the organization must first take into consideration what is best for the children, families and communities Eckerd serves — the Hub of the Eckerd Wheel. Second, any course of action must stay in balance with the five Spokes. For example, if Eckerd is evaluating whether or not to pursue a new program, it could be that the program can be operated with strong performance (Quality), can generate sufficient margin (Finance), has a good potential partner in the funder (External Relations) and is an improved adaptation of the existing service model (Growth & Transformation). The program also may fit a need for the families in the local community (Hub). While those boxes can be “checked off,” the program’s location might make it difficult to hire qualified staff, creating notable risk. Until this Spoke imbalance is fixed, Eckerd would not pursue the program. The Eckerd Wheel has enabled Eckerd to weave its values deeper into its operational fabric.

Strategy is nothing without execution

Knowing where you are going and why, and understanding who does what and the resources needed, is crucial. To shape Eckerd’s strategic approach and ensure its execution, the CEO created a Chief Strategy Officer (CSO) role reporting directly to him. A former military officer and electrical engineer who had been with Eckerd four years assumed the position.

Eckerd focused on keeping things simple as it developed its strategic approach. What emerged was a document that told the story of where Eckerd had been, where it was going and how it intended to get to its 2020 Vision of serving 20,020 clients annually. The focal point was a one-page Strategic Snapshot that brought together Eckerd’s near-term goals, building blocks and strategic execution paths — oriented around the Spokes of the Eckerd Wheel. Since 2007, near-term goals have been updated every two years, with ongoing key performance indicators (KPIs) updated monthly in partnership with the Executive Leadership Team.

Never stop adapting

Management consultant Peter Drucker once said, “An organization that is not capable of perpetuating itself has failed.” Eckerd was nearly “boiled” because it lost its capacity to adapt, replacing it with its passion for operating camps.

Eckerd established the Growth & Transformation (G&T) Spoke of the Eckerd Wheel to ensure it would always be an organization that was perpetually searching for ways to adapt and transform. To put it another way, Eckerd wanted to always have the courage to change.

The G&T Spoke has led to two major transformations. First, Eckerd forged ahead with closing its camps and seeking out community-based services. In 2008, Eckerd provided minimal child welfare (foster care) services. Florida, where Eckerd was founded and operated many of its services, contracted with nonprofits to act as “Community-Based Care (CBC) Lead Agencies” overseeing the delivery of child welfare services across the state. While Eckerd did not have much child welfare experience, its CEO had run one of Florida’s CBC regions and had forged deep relationships. Eckerd became aware that a contract was being removed from a local CBC agency and saw this as an opportunity to jump-start its transition to community-based services, as the CBC contracts were substantial ($20 million to $60 million in annual revenue). Additionally, CBC operations were highly data-driven, a skillset Eckerd was lacking that would help establish a culture of data. After six months of planning and personnel investments, Eckerd was selected as the winner of a $50 million annual contract. It was Eckerd’s first notable venture into the community-based space.

The second transformation was moving further “upstream” to provide more prevention-oriented services. Eckerd realized that while community-based services delivered better outcomes at a much lower cost than their residential peers, they did not address a fundamental instability that plagued many of the families being served in the juvenile justice and child welfare systems: financial insecurity. To address this critical challenge, Eckerd decided to make another strategic shift and enter the workforce development space to help youth and families experiencing financial insecurity obtain gainful employment.

Expand deliberately

In 2014, leadership and the Board began actively accelerating Eckerd’s transition with a series of mergers and acquisitions. Prospective partners were carefully selected based on how they fit into Eckerd’s overall strategy for expansion. Since then, the organization’s pace of growth has remained steady but deliberate.

Over the next five years, four major transactions were completed totaling roughly $126 million in new annual revenue. More important, these M&As brought many talented staff members, enabling Eckerd to expand its impact. Since then, Eckerd has won, through competitive bid processes, $25 million in additional workforce services, bringing Eckerd’s total workforce program footprint to $150 million, or 43% of Eckerd’s total revenue.

Eckerd’s first acquisition was in 2014, when it acquired Caring for Children, a $3 million Asheville, N.C.-based nonprofit child and family services provider. The following year, Eckerd acquired Paxen, a $10 million for-profit workforce development provider operating in five states.

Eckerd’s strategy of moving upstream meant targeting kids who might be in crisis, but who were not yet in the justice system. The area of workforce development aligned with Eckerd’s core values and served a similar group as its camps — marginalized young adults from ages 16 to 24. In addition to meeting a need in communities and replacing some of Eckerd’s lost revenue from closing its camps, these acquisitions allowed Eckerd to compete for future government contracts in those states as an entity with a local presence. Eckerd paid no money for either company — however, as part of the acquisition arrangement for Paxen, it did agree to take on the company’s existing debt.

Assimilating these existing companies and their 130 employees into the Eckerd organization brought unforeseen challenges, but Eckerd’s leadership team viewed each acquisition as a learning opportunity from which to build better processes. As part of the Paxen deal, for instance, Eckerd held a three-day retreat with Paxen’s management team to answer questions and educate them on the organization’s history, culture and working processes.

Eckerd’s next growth opportunity came in 2016, when engineering firm Henkels & McCoy (H&M) offered to donate a training services division that primarily bid on government workforce development contracts. This arrangement benefited both companies, allowing the division’s mission-driven work to continue and all of its employees to stay on the job. Eckerd, meanwhile, added $18 million in annual revenue and further expanded its reach in the workforce development space.

Though each of these M&A deals was larger than the one before, Eckerd’s $96.4 million merger in 2020 with Arizona-based workforce development organization Odle Management Group was on a different level entirely. Odle manages workforce development campuses across nine states that provide nearly 15,000 young adults with a range of residential, academic, and career preparation and job placement services. Unlike Eckerd’s previous acquisitions, Odle was a for-profit business, meaning that the M&A process was more complex and required money changing hands.

Eckerd drew upon its previous acquisition experience and also sought the assistance of M&A professionals to make the case for the deal to its board of directors, acquire a bank loan and bring Odle under the Eckerd umbrella — making sure that employees feel valued and invested in the company’s continued success.

These expansions represented a small portion of the roughly 50 growth opportunities that Eckerd was presented with during this period. As with any other decision made by the organization, these opportunities were evaluated on whether they stayed in balance with the five Spokes of the Eckerd Wheel and had the potential to benefit the clients and communities served by Eckerd. Those that weren’t the right fit for any reason were not pursued.

Empathy is essential

By the end of the new CEO’s first few months, 30 positions had been eliminated at Eckerd’s headquarters (renamed the Support Center), and the tough conversations about the camps had started. Many staff, some with Eckerd for decades, felt aggrieved, which only intensified after the first camp closed. Several Board members lamented the loss of beloved programs. Staff members worried about their futures.

The stress of change can become overwhelming for staff and Board members. But despite the discomfort, nonprofit leaders must never shy away from making difficult decisions. They must do what is best for the people they serve and for the perpetuity of the organization. When they decide on a course of action, they need to communicate their decision and the reasons why to their Board and staff expeditiously, in full transparency and with deep empathy. They must do their best to attend to the emotional needs of those directly and indirectly impacted, as each may be experiencing anger, sadness and fear. This means listening more than talking. It means recognizing the other person may be speaking from a place of high emotion and should be given grace. It means answering questions truthfully but with gentleness. And it means, no matter what, treating others with dignity and respect.

The middle is messy

Bestselling leadership author Robin Sharma once described change as “hard at first, messy in the middle and so gorgeous at the end.” This is a key lesson of Eckerd’s story. Fairytale-like stories of successful turnarounds are common, but what isn’t as frequently discussed is the ugly underbelly of these journeys.

There is a certain nervous euphoria when launching a venture, and if one is fortunate enough to land with success, sometimes “amnesia endorphins” get released that magically erase the pain of what happened between launch and landing — that is, the “messy middle.” Entrepreneur Scott Belsky, in his book The Messy Middle, makes the case that it is the journey in between that determines victory or failure, and he stresses that self-awareness in times of difficulty, and success, is vital to surviving.

The middle part of change is a rollercoaster of volatility. Each day is a struggle. Emotions are up and down, tempers flare, patience wears thin and physical exhaustion rears its head. Everything is urgent, whether it should or not. The pace is so furious that personal priorities get neglected, all of course with well-intended justifications stemming from the mission at hand. The scales of work/life balance tip toward work, and everyone’s life suffers unless self-awareness is maintained.

It is understandable to not want to talk about the messy middle, because much of the turmoil and stress is due to a lack of self-awareness — meaning, to an extent, that it is self-imposed. Eckerd initially did not maintain a high level of self-awareness during the messy middle, and it took its toll. Thankfully, with time, the team recognized this and committed itself to finding a better balance between work and life.

As Eckerd continues to write its story, we hope the lessons we have learned can help others avoid, or if needed escape, their own figurative boiling pot. Please take care of yourself, your team, and your mission, and thank you for fighting the good fight.

Download White Paper